73. Zen & Design: Skillful Means

SUBSCRIBE TO UNMIND:

RSS FEED | APPLE PODCASTS | GOOGLE PODCASTS | SPOTIFY

What is the problem?

Buddha defined it as Dukkha —

I say Upaya.

We launched the UnMind podcast the third trimester of 2020, in the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic. Running through the end of 2021, they featured various individual episodes and series of commentaries on selected historical teachings of Zen Buddhism from India, China and Japan. We wrapped up with Matsuoka Roshi’s excellent overview on finding your way amongst the Zen ways, “Dhyanayana,” from Mokurai, the collection of his later talks from the 1970s and 80s. A most appropriate conclusion to the year, as he compares and contrasts various Zen approaches, recommending Soto Zen as the upaya, or skillful means, of our times. Of course, Sensei was somewhat biased in this regard, but he had an informed grasp of Rinzai and other Zen pedagogies on offer in Japan as well as the West. His focus was on isolating the vehicle best suited for our times. This is in line with the founder of Soto Zen in China, Tozan Ryokai, as reflected in his Ch’an poem Hokyo Zammai, Precious Mirror Samadhi:

Now there are sudden and gradual in which teachings and approaches arise

With teachings and approaches distinguished each has its standards

Whether teachings and approaches are mastered or not reality constantly flows

The operative phrase here is that last: “reality constantly flows.” By recommending Soto Zen’s direct approach through upright seated meditation, zazen, Matsuoka Roshi directs our attention to the reality that is constantly flowing in front of our face. However diverse the choices served up on the spiritual smorgasbord of modern meditation in America, and however interesting the times in which we live, zazen is the most skillful means for dealing with the real koan presented by everyday life.

When we consider Zen’s central focus on zazen rather than, say, the koan practice of the Rinzai approach, we can evaluate it scientifically as a method. But like aerobics or calisthenics, we have to experience Zen meditation directly in order to clearly understand and appreciate how it works. Simply sitting still enough for long enough that the effects of zazen begin to set in place, whether sudden or gradual, short- or long-term, is irreducibly simple. But it entails some complexity on both personal and social levels.

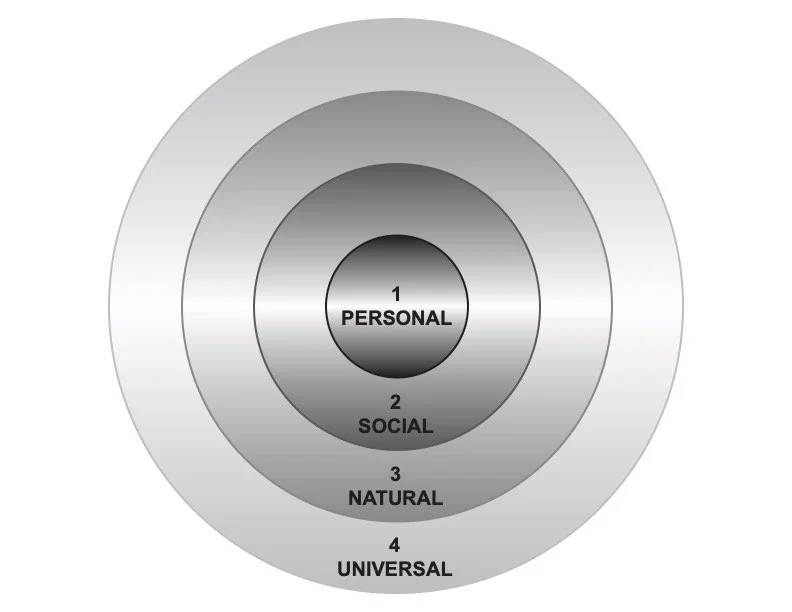

In this new year, we introduce a departure from our past approach to the UnMind podcast. We will explore the intersection of design thinking and Zen practice, including creativity in general, the inflection point and perspective from which I have lived most of my life. In this new set of fifty or so episodes, we set the context with a model of the world as manifested in four concentric spheres, from the inner personal sphere to the outer social, natural, and universal spheres. Reality is constantly flowing in and through the interfaces of all four, as interactive spheres of influence.

Meditation is located in the inmost sphere, our personal intimate bubble. Here we find the posture, breath and attention of zazen, in O-Sensei’s tripartite breakdown. Likewise, you can locate the other dimensions of the Eightfold Path within each of these spheres, some crossing the boundaries between. The Three Actions of Buddhism are said to be of body, mouth and mind, bridging the personal and social, with some effect in the world of nature.

Sensei’s simple three-point model of Zen’s intentional-attentional approach to meditation includes a fourth point, namely yourself. This quartet completes a triangular pyramid, the simplest of regular geometric solids, in the three-pointed base of the cross-legged posture, with your head at the apex. A tetrahedron is the most stable of forms found in nature, such as molecules of carbon, which can manifest as soft as soot or as hard as diamond. Assuming the posture brings its stability into your life.

Crossing the boundary zone into the next sphere out, the surrounding social milieu, there arises the practical matter of finding time for zazen in the midst of our modern, hectic schedules. Add to that the social issue of how it affects our relationships at home, at work and elsewhere. Since we are not monastics, the world of the householder is the environ of our practice, extending to the workplace and other locales. In effect, it constitutes our monastery without walls.

Most of the friction in daily life is found at the boundaries between the spheres. The interface of the social with the natural is the inflection point of our current struggles with pandemic, and looming disasters associated with climate change. This is the passing pageantry of life, the backdrop to Zen.

The method of Zen, centered around zazen, is taken up as skillful means. This expression primarily refers to the pedagogy by which the ancestors transmitted Zen practice to their students. But the various means by which this transpired constitute a problem-solving activity. The example of the teacher is necessary to developing an appropriately receptive attitude toward the potential of leading a Zen life. But this is not the Zen of pop culture, so-called American Zen, but of Zen Buddhism, the genuine article. Including how and where it all started with the historical Buddha. The original Order in India was an experiment in intentional community, a radical departure from the caste system of the time, structured around the practice of meditation. As such, it was a design initiative.

There are many dimensions where Zen and design thinking overlap, particularly in the design of zazen. Various sub-routines such as counting the breath, posture correction, and walking meditation become natural extensions of Zen meditation. Zen protocols form bridges between the personal sanctuary of sitting and the social necessity of taking action in the world. Balance and centering, stillness or samadhi, is key to outcomes in both. Zazen itself is the most we can do to actualize “engaged Zen.”

Design done right is also a way of engaging the world and, like Zen, has developed an entire philosophy as a side-effect. Professional design training emphasizes skillful means in the form of sophisticated problem-solving schema. I was exposed to this worldview in my late teen years at the Institute of Design, Illinois Tech, under the rubric and tutelage of what is known as the Bauhaus method. Its origin was in the famous pre-World War II school in Weimar, Germany. Just as zazen is a process of immersing ourselves in our own sensory awareness, design-build activities require immersion in materials, tools and deliberate processes, both innovative and productive. Both methods are empirical.

Design and Zen both go beyond their popular misconceptions. Design is often relegated to interior design as dealing only with surface appearance, merely manipulating decorative materials, form and color to achieve a more pleasing aesthetic effect, basically superficial. But like Zen, design as a way of engaging reality goes deeper. It penetrates to the level of functionality, the essential underlying activity. “Form follows function” is a precept of design, akin to Master Dogen’s principle of zenki, “total function.”

Comparing design thinking with Zen’s non-thinking, a host of congruent concepts, parallel processes and shared values becomes startlingly obvious. Beginning with intensive personal investigation of media and materials, whether inborn as body-and-mind in Zen, or those of the external world in design, the scope of application and resultant sphere of influence in each area naturally expands over time.

R. Buckminster Fuller, an exemplar and mentor to several generations of design professionals, called his process “comprehensive anticipatory design science.” His work influenced broad segments of society, with unique contributions to the educational and architectural fields, to the mathematics of engineering characterized by his iconic domes, including early design programs targeting the stewardship of global resources. His disciples are continuing these traditions yet today.

Both Zen and design disciplines entail individual effort as well as group collaboration. Designing and redesigning the most efficacious processes in each requires experimentation and creativity.

We will continue this line of thinking in the next episode. Meanwhile, look at what Buddha did. What problem did Buddha solve, would you say? Or what problem did he define?

Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston

Elliston Roshi is guiding teacher of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center and abbot of the Silent Thunder Order. He is also a gallery-represented fine artist expressing his Zen through visual poetry, or “music to the eyes.”

UnMind is a production of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center in Atlanta, Georgia and the Silent Thunder Order. You can support these teachings by PayPal to donate@STorder.org. Gassho.

Producer: Kyōsaku Jon Mitchell