110. Student vs Teacher

SUBSCRIBE TO UNMIND:

RSS FEED | APPLE PODCASTS | GOOGLE PODCASTS | SPOTIFY

Not symmetrical

But then nothing really is —

Only in our mind

In this segment of UnMind we continue where we left off, discussing the all-important mentoring relationship of teachers to students, and students to teachers, particularly the asymmetrical relationship in Zen training. The success of any mentorship depends almost entirely, 100% plus, on the sincerity and intensity of the student, more so than the teacher, as illustrated by the anecdote about my friend and fellow student at ID+IIT, JJ, who had an unfortunate run-in with one of my key design mentors related in the last segment. As a teacher of design at the U of I, Chicago Circle Campus, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I found myself on the other side of the equation and gained even more respect for my mentors. For those design students who did not seem to benefit greatly from my tutelage, I can fault them as well as myself. My story and sticking to it, anyway.

The well-known exchanges between Zen ancestors and their students, particularly those who eventually succeeded them in the lineage, are illustrative of this asymmetry. Bodhidharma, the first Zen patriarch known to history in China, for example, responded to his Chinese student and dharma heir, Huike, who complained of having a disturbed mind, by asking him to show him this mind. When Huike replied that when he looked for it he could not find it, the sage exclaimed “There I have calmed your mind!” or some such expression. These incidents are variously translated so please forgive my paraphrasing, as well as the spelling of the names. I am not a scholar.

My point here is that then Huike, in a similar exchange with his future successor, Sengcan, said something similar. The eventual third patriarch in China likewise complained of being “bound” by something, and Huike asked him what was binding him. When he could not respond, Sengcan suddenly realized there was nothing binding him and was liberated.

That Huike responded to his student in essentially the same way that his teacher Bodhidharma had replied to him illustrates that the teacher was not called upon to say or do something extraordinary, but instead had responded with an ordinary, mundane question. We might even conclude that Huike had merely imitated Bodhidharma’s approach. I think this makes the case that what triggered the profound event of the student’s transformative insight was not the skill or mystical power of the teacher, but was dependent upon the desperation of the student, combined with complete faith in the teacher.

Symmetry is a principle of Design Thinking, as can be seen in the design of most modern automobiles as well as vintage wheeled vehicles, such as the chariot Buddha used as an analogy to the skandhas, or the Conestoga wagons that settled the West. The practical reasons for this are pretty obvious when considering the function of the vehicle to move straight forward or backward in as friction-free a way as possible, as well as to navigate turns. But the adherence to symmetry in design goes far beyond the practical functioning of the vehicle, into the aesthetics of its overall form and features. One of the few notable exceptions to the symmetry norm may be seen in the Nissan Cube (see photo) introduced to the American market in 2009 and discontinued in 2014. We may most usefully consider this anomaly in the context of the adage, “form follows function.”

Seeing this startling design for the first time may cause whiplash as it surprises your expectations of symmetry. It features a wrap-around window on the rear and one side, which violates the usual bilateral symmetry of vehicle design. I wonder if it also created a hazard in case the vehicle rolls in a wreck, as the roof-support structure would apparently be greatly weakened by the lack of a fourth column in that corner. And that that partially explains its brief time on the market.

Of course, the power drive chain and other mechanical systems that make the modern vehicle function are not symmetrical in the simple sense – one only has to look under the hood to see the asymmetrical complexity of the modern combustion engine or that of the newer electric and hybrid vehicles.

The apparent bilateral symmetry of the human being and many other animals is similarly deceptive. Once the relatively symmetrical outer appearance is removed, as in surgery or an autopsy, the incredible complexity of the underlying system of nerves, glands, and organs is revealed. The skeleton and musculature largely reflect the symmetrical form of the outer appearance, and much like the drive train and wheels of the automobile, function to support the mobility and balance of the body in motion.

So the appearance of bilateral symmetry in both cases is just that – appearance, another word for form.

The famous formula coined by Buddha, that form (appearance) is, itself, emptiness — and vice-versa — reflects this greater reality. If we probe even further, down to the molecular and atomic levels, it becomes clear that while the constituent elements making up the appearance of symmetry of the object may themselves exhibit various kinds of internal symmetry, including radial and other three-dimensional geometries that transcend mere bilateral or mirror symmetry; there is no clear, fractal-like relationship of the micro-scale parts to the macro-scale whole. The forming processes of whatever metal, plastic, rubber, textile and other materials undergo in order to achieve the final form of the completed object obviously depend upon the properties of the materials, but their original, internal form has little to do with the final, external form. Like the fabled chariot, the whole exists only in the sum of the parts.

If we deconstruct the vehicle, like the chariot, it ceases to function, or to exist, as a vehicle. Likewise, the organism, human or otherwise, does not function or exist outside the particular assembly of its parts. Zen meditation is often referred to as a process of deconstructing consciousness, or the mind itself. Realization, according to Master Dogen in Jijuyu Zammai—Self-Fulfilling Samadhi, is the manifestation of this process (emphasis mine):

All this, however, does not appear within perception because it is unconstructedness in stillness; it is immediate realization.

Note that the term “unconstructedness” does not even qualify as proper English; the giveaway is the red underline the word processor uses to highlight a mistake. Dogen goes on to point out that “if practice and realization were two things, as it appears to the ordinary person, each could be recognized separately. But what can be met with recognition is not realization itself because realization is not reached by a deluded mind.” This indicates that anything that can be met with recognition is, by definition, a kind of delusion. Our very recognition of something we call “symmetry” is itself delusional. Upon closer examination it falls apart, seen to be, at best, a kind of approximation. The mind continually averages out all the contrary impressions of asymmetry to focus upon and reify the notion of symmetry.

The immediacy of realization the Master points to should be understood as immediate in both time and space. That is, in this “realization” what becomes real to us is not something that heretofore was distant from us and somewhere in the future, but always and ever present, and near at hand. So close as to be inaccessible to perception as such, like the water to the fish, or the air to the bird. As Dogen points out later in this same tract, even the idea of “realization” must be regarded with some circumspection:

[But] the boundary of realization is not distinct. For the realization itself comes forth simultaneously with the mastery of buddha-dharma. Do not suppose that what you realize becomes your knowledge or is grasped by your consciousness. Although actualized immediately, the inconceivable may not be apparent. Its appearance is beyond your knowledge.

That “the inconceivable may not be apparent” — one of my favorite Dogen lines and, I think, indicative of his sense of humor — must be one of the grand understatements of all time. How could the inconceivable in any way be apparent? This is one of the hallmarks of the asymmetrical nature of the relationship, the ability to use language but not be used by it. So to speak. o point at that which is beyond concept, let alone language. Concepts take time to form. Expressing them in language takes even longer. Using words to point at that which is beyond conception, and thus far beyond language, is difficult, but not impossible. Tozan Ryokai, credited with founding Soto Zen in China, reminds us of the inconceivable nature of Zen realization in his Ch’an poem Hokyo Zammai—Precious Mirror Samadhi, pointed to as “it” (J. inmo):

Although it is not constructed it is not beyond words

Like facing a precious mirror

Form and reflection behold each other

You are not it but in truth it is you

It would be hard to find a more succinct and intriguing description of a symmetrical relationship than “Form and reflection behold each other.” Especially as the two elements of the sentence, “form” and “reflection,” indicating object and subject, respectively, are usually considered to be the opposite of symmetrical — comprising the material and spiritual dimensions of existence — or matter versus mind.

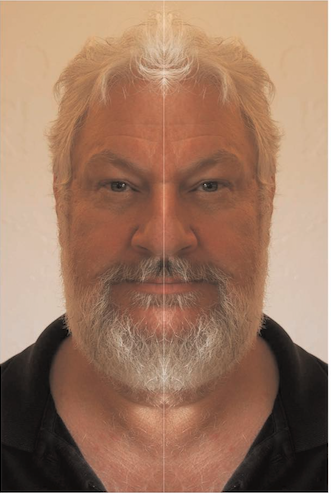

One more visual example of the apparent symmetry versus the actual asymmetry that we normally perceive is illustrated by an exercise called “Your Original Face” from a creativity workshop we conducted at ASZC, based on Huineng’s famous anecdotal koan. In the photos you see the same portrait of my face, divided down the middle axis and reconstructed to reveal the “left-face “ versus the “right-face” version of me. Looks like me, but… Note that the arched-eyebrow side in shadow connotes the evil me while the side in full light looks more like a saint. The “eyes have it” but so do the eyebrows and mouth.

Problem-solving is the action-oriented modus operandi of both professional design thinking and the Zen or Buddhist worldview. Designers define problems worthy of solving, often redefining those presented by clients, for financial as well as altruistic reasons. Siddhartha Gautama clearly interpreted the cultural norms, mores and memes of his times and his particular social standing in the caste system as problematic or unsatisfactory, and went on what we might romanticize as a spiritual quest to find a solution. His findings, conclusions, and recommendations constituted the content of the First Sermon, in which he laid out the Four Noble Truths, an extremely concise and complete description of the “problem” of sentient existence, particularly for human beings, including a thoroughgoing prescription for practicing in daily life, the Noble Eightfold Path, which, crucially, emphasizes the central method by which anyone can approach and — at least in theory — solve this problem for themselves, essentially by “doing thou likewise.”

Fortunately for us, he succeeded to a greater degree than most of his contemporaries. He and his followers transformed this personal experience into a socially inclusive program for like-minded people, the original Order of monks and nuns, as well as householders and leaders, in India. This is the origin of the legacy we have inherited and celebrate today.

As I said in the prior segment, in both design and Zen training, relationships to your mentors become all-important, shaping your views of the profession, and the practice and meaning of meditation, respectively. This is true of Zen in particular, and probably all asymmetrical relationships in general. Where we go from here we shall see, as we say, but wherever the road takes us, it will arrive at the intersection of Zen and Design Thinking. Meanwhile keep practicing.

Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston

Elliston Roshi is guiding teacher of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center and abbot of the Silent Thunder Order. He is also a gallery-represented fine artist expressing his Zen through visual poetry, or “music to the eyes.”

UnMind is a production of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center in Atlanta, Georgia and the Silent Thunder Order. You can support these teachings by PayPal to donate@STorder.org. Gassho.

Producer: Shinjin Larry Little