105. Design & Zen Summary V

SUBSCRIBE TO UNMIND:

RSS FEED | APPLE PODCASTS | GOOGLE PODCASTS | SPOTIFY

It’s not personal.

But it manifests that way —

Universally.

As promised in the last segment, we will finish this series of five by taking up the remaining pair of combinations — the intersection of the Personal from the Four Spheres, with the Cessation of suffering from the Four Noble Truths, which involves the Eightfold Path previously touched upon. Personal Cessation is the only kind there can be, it seems. Even the Natural Cessation of physical death is not considered the end of suffering in Buddhism, owing to the principle of rebirth. Social Cessation does not seem that germane, other than the relatively decreasing engagement that comes with aging. But ask anyone in assisted living, palliative or hospice care, and you will find most of the issues that arise are social in nature. It must be admitted that if Cessation of suffering can and does actually occur in the midst of life, it must be a Universal phenomenon, as well as Personal. But the only dimension that counts must be the Personal, i.e. how we actually experience and embrace it.

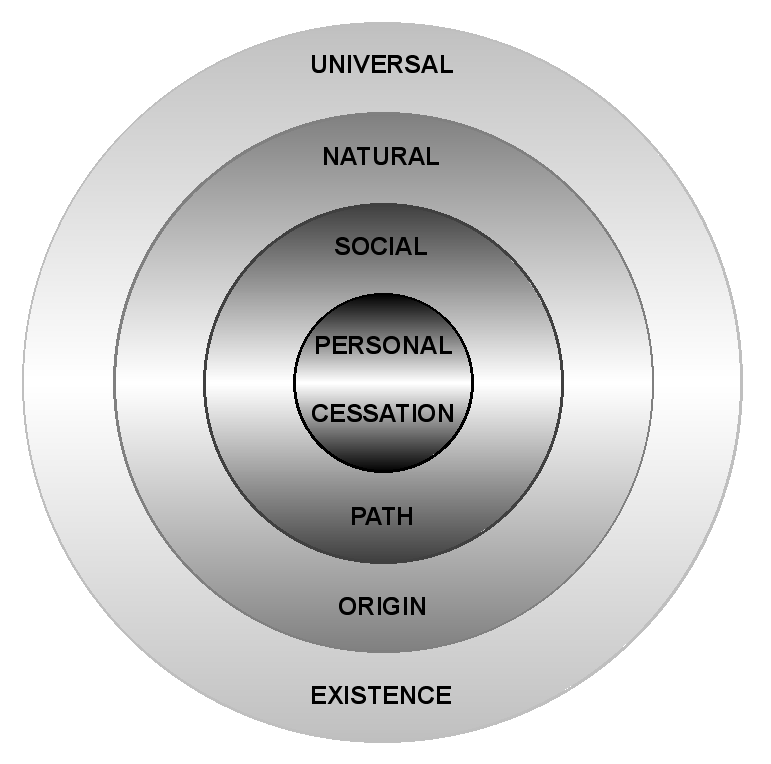

The graphic illustrates the correlation of the Four Spheres of reality — the Personal, Social, Natural and Universal — with the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism — the Existence, Origin, Cessation, and Path to Cessation, of suffering, dukkha, a comprehensive model of lay Zen householder practice.

The Personal sphere is the bubble in which we sit when we assume the zazen posture. As mentioned, we do not thereby totally leave behind the Social, any more than we can escape the Natural and Universal spheres of influence, notwithstanding ancient claims to the contrary for the powers of meditation. But we can establish some distance between ourselves and others in meditation. Master Dogen hints at this in Fukanzazengi [Principles of Seated Meditation], his early tract on zazen:

Now, in doing zazen it is desirable to have a quiet room. You should be temperate in eating and drinking, forsaking all delusive relationships.

The operative phrase here is “forsaking all delusive relationships,” which begs the question: Which, if any, of the many relationships we have are not delusive? In another teaching, Genjokoan [Actualizing the Fundamental Point], Dogen lays out four transitions in Zen practice in descriptive, but cryptic, terms:

To study the Buddha way is to study the self

To study the self is to forget the self

To forget the self is to be actualized by the myriad things

When actualized by the myriad things your body and mind

as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away

No trace of realization remains and this no-trace continues endlessly

Another translation says something like: “to forget the self is to be enlightened by all things; to be enlightened by all things is to remove the barrier between self and other and go on in traceless enlightenment forever.” This can be misinterpreted, I think, to indicate that this realization is a kind of “kumbaya” moment, where we see and embrace the fact that we are all alike, all in the same boat, et cetera, and why “Can’t we all just get along?” In other words, a Social interpretation of self and others, plural, and removing any apparent barriers. But I do not think this is what Master Dogen is getting at.

If instead we “remove the barrier between self and other,” singular, this identifies the fundamental relationship that we have to resolve, above and before all others. Like Bodhidharma alone in his cave, self-and-other are still present. This basic bifurcation in our apprehension of reality is akin to the Fall from Grace in Buddhism. It amounts to a kind of category error, one that develops in early childhood via the natural process called individuation, i.e. becoming aware of ourselves as individual beings separate from mom, the crib, and everything else. This is further reinforced by parents, teachers and peers, in conventional education. Which, in our culture, does not typically include meditation.

Not that this growing awareness of separate individuality is not true; it is just that it is not complete. The rest of the story is that we are intricately interconnected to all of our relationships, including with other human beings, but also sentient beings of other species in the animal kingdom, as well as plant life, and the insentient world. In other words, the Personal cannot be isolated from the Natural and Universal, let alone the Social. Master Dogen goes on to suggest that in zazen, however, we suspend judgment about all of this for the moment, at least for the time we are on the cushion:

Setting everything aside, think of neither good nor evil, right or wrong. Thus having stopped the various functions of your mind, give up even the idea of becoming a Buddha.

Note that “everything,” here, primarily entailing those judgment calls in the Social sphere, such as identifying “good and evil, right and wrong,” are to be set aside, in zazen. And that this kind of thinking represents the natural functioning of the mind, that is, the thinking or discriminating mind, known as citta in Sanskrit, the complement of bodhi, or wisdom mind. I think we can define these terms simply as analytical versus intuitive aspects of the total mind, or bodhicitta. This basic division of the mind into a dyad, or binary, we may take as the psychology or mind science of the times, as compared to the more complex models of the brain and its functions propounded by science today.

The main point here is that the ordinary functions of the mind —which we advisedly tend to label as “monkey mind” — reach a point of diminishing returns, though I don’t think we can literally stop them. Like a live monkey, citta will eventually wear itself out, lie down and take a nap. Trying to stop the functions of the mind intentionally only turns out to be more monkey business, as in the Ch’an poem Hshinshinming [Trust in Mind]:

Trying to stop activity to achieve passivity, the very effort fills you with activity

This is one of the many catch-22s that we find in Zen practice. And not only on the cushion, as Dogen goes on to remind us:

This holds true not only for zazen but for all your daily actions.

So the Personal Cessation of suffering may be experienced not as a sudden, irreversible event, like a thunderbolt from the sky, but a series of gradual, incremental cessations of our knee-jerk reactions to events. Both in the Personal sphere, particularly in meditation, as well as interactions with others in the Social and Natural spheres. This attitude adjustment may extend to other forces in the Universal realm, such as the effects of climate change. Or something as simple, but potentially deadly, as a sunburn.

One premise that has to be reinforced from time to time in Zen and other meditation circles, is that our practice does not, and cannot, reveal anything that is not already true. Meditation does not and cannot change anything, other than our personal apprehension and appreciation of our own reality. The revered Zen Buddhist saint, Bodhidharma, declared that it is not necessary to do zazen in order to “grasp the vital principle.” Which tells us that we do zazen for some other reason, namely to set aside all delusive relationships, for one example. Which suggests that we must be harboring a lot of delusive relationships, whether we are aware of them or not. Otherwise, why does zazen require so much time?

As I mention in The Original Frontier, the first reason most people give as to why they cannot do meditation, is that they do not have time. This is mainly because they look for immediate results, and give up when the novelty wears off, and they cannot detect sufficient positive feedback to encourage them to continue. According to the principles of zazen, and Personal Cessation, meditation does not necessarily take any time at all to take effect. Since we are getting in our own way, all we have to do is stop. Aha, you say — but that’s how they get you. Catch-22 déjà vu.

If the Cessation of suffering writ large is dependent upon case-by-case Personal Cessation of all those habits of thought and behavior that are getting in the way, how do we recognize and identify them, and relinquish our attachments or aversions to them that keep dragging us down? I think one of the key attitude adjustments is to recognize that we are not only receiving, but interpreting, our experience, even at the near-subliminal level in zazen. If we can set aside any interpretation at all — let alone judgments of good and evil, right and wrong, at least while we are on the cushion — then maybe we can move that dharma gate a little.

One last consideration before we leave this perhaps overly convoluted analysis of the intersection of the Four Noble Truths with my model of the Four Spheres of Influence, suggests another connection with the teachings of Buddhism. The spheres of internal and external reality correlate with the Three Treasures of classical Buddhism. Buddha, Dharma and Sangha track to the Personal, Universal and Social spheres. Briefly, Buddha — indicating practice on the cushion as a practical matter, but also our original nature, or birthright as human beings — is obviously a very Personal dimension of Zen practice. Of course, in light of its deeper connotations as “original nature,” it has Universal and Social implications. The study of and propagation of Dharma clearly involves a Social program of education — or “sharing the dharma assets,” expressed as a Precept — but also a Personal endeavor, climbing the Zen mountain. Again with Universal implications as Dharma, capital D, as the Way, or Tao, the law that governs the universe. Sangha is most obviously Social in character, but also Universal, representing the entirety of the human species from its origins hundreds of thousands of years in the misty past, to its current manifestation in facing the looming possibility of the Anthropocene Extinction, the sixth such global catastrophe on record. I could go on. But it is time to shift to another paradigm.

Meanwhile, please continue practicing in the holistic context of the Four Spheres and the Four Noble Truths, as well as the Three Treasures. Climbing Zen Mountain, and then descending.

Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston

Elliston Roshi is guiding teacher of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center and abbot of the Silent Thunder Order. He is also a gallery-represented fine artist expressing his Zen through visual poetry, or “music to the eyes.”

UnMind is a production of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center in Atlanta, Georgia and the Silent Thunder Order. You can support these teachings by PayPal to donate@STorder.org. Gassho.

Producer: Kyōsaku Jon Mitchell